Table of Contents

Message from the Superintendent/President 3

Introduction 4

Overview and College History 6

Mission, Philosophy, Purpose, Principles of Community and Visional Educational Values and Goals 7

Environmental Scan- External to the College 9

Environmental Scan- Internal to the College 41

Institutional Effectiveness 88

Institutional Performance Expectations 88

Institutional Performance 93

Student Institutional Learning Outcomes (ILO) 108

Interventions 111

Grant Resources to Support Interventions 111

Ongoing Resources to Support New Interventions 121

Opportunities for the Future 122

Future Labor Markets 122

Planning for Potential New Programs 126

Faculty and Staff Visions for Curriculum and Delivery of Support Services 127

Opportunities for New Initiatives, Improvement or Expansion of Programs 145

General Areas of Opportunity 145

Possible Areas of Policy and Practice Modification 154

Possible Areas of Curriculum Expansion/Modification 161

New Career and Technical Education Possibilities 164

Key Planning Assumptions, Goals, and Strategic Priorities 168

Planning Assumptions 168

Visionary Educational goals and Strategic Priorities of the College 171

Strategic Priorities of the College 171

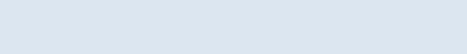

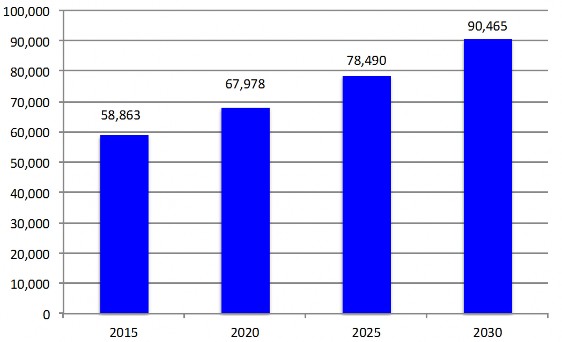

Projections for Future Growth 172

Future Capacity for the Growth 172

Baseline Term Analysis 175

WSCH Projections and the Future Program of Instruction 180

Space Projections 181

Acknowledgements 183

Appendix Materials 187

Appendix A- Neighboring Colleges and Distances 187

Appendix B- Industry Employment and Labor Force by Annual Average, 5-Yr Increments 188

Appendix C- Degrees and Certificates Related to Distance Education Substantive Change Proposal 191

Appendix D- Online Services and Forms Available to Students 193

Appendix Grant-Funded Intervention Summaries 203

Appendix Grant-Funded Interventions: Crosswalk of Major Intervention Effort Attributes 221

Appendix PM- Gavilan College Programs Matrix 223

Appendix SP- Gavilan College Strategic Priorities and Goals 224

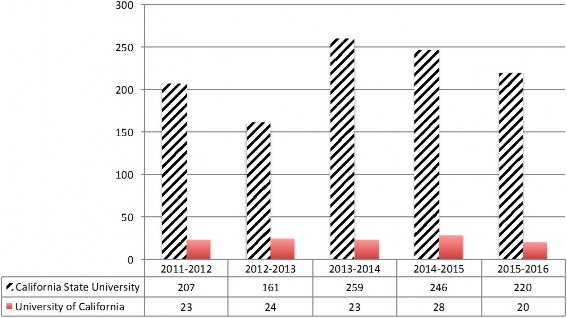

Appendix T1- CSU Transfer Students from Gavilan, Major Field of Study 228

Appendix T2- UC Transfer Students from Gavilan, Major Field of Study 229

Appendix JOBS: Occupational Projections 230

Appendix X- WSCH Projection Details 2015-2030 246

Appendix Y- Space Projections Detail 2015-2030 252

Gavilan College has been serving the higher education needs of San Benito County residents since 1919, and South County residents since 1964. We have grown to be a 2,700 square-mile district with five locations and comprehensive instructional programs in numerous disciplines.

Throughout that history, we have periodically reflected on our practices and educational programs to ensure they remain relevant and continue to meet the academic and workforce needs of our community. With a new Superintendent / President on board, and a rapidly changing external environment, it is once again time to assess our operations and facilities in light of community goals. This Education Master Plan is a comprehensive review to determine how our curriculum, campus, and infrastructure will meet the current and future needs of our students. This document represents the findings of a thorough analysis of our strengths and opportunities for the future.

Gavilan College faculty and staff have done tremendous work to open our new Coyote Valley and San Martin locations, develop 22 Associate Degrees for Transfer, and to provide innovative Student Services for student success.

Our Career Technical Education division and Community Education department have worked together to bring on career training programs such as Water Resource Management, Unmanned

Aircraft Systems, and Hospitality Management.

This Educational Master Plan highlights some opportunities going forward – working with our community to build a “college-going mindset,” exploring a College Promise program, developing Guided Pathways, and assessing the potential to serve international students. In the areas of career training, there is potential to expand a business focus with customer service and business information worker training, and to support local manufacturers with advanced manufacturing and welding programs.

The completion of the Education Master Plan is just the start, however. It serves as a blueprint and will inform the district’s Strategic Plan, the Facilities Master Plan, and all of the action plans that will lead to enhanced student success. With the strong leadership of our Board of Trustees and the on-going support of our diverse communities, the future of Gavilan is exciting and truly portrays a college that is on the move!

Thank you for being a part of our journey.

Kathleen A. Rose, Ed.D. Superintendent/President

During the academic year 2016-2017 the Cambridge West Partnership, LLC (CWP) was invited to assist the College in developing a new Educational Master Plan (EMP). The purpose of the EMP is to explore the ways in which the College’s curriculum options might be optimized to match labor market needs, increase transfer opportunities, and align with community educational needs/interests. A second purpose of the EMP is to provide a projection of future attendance that can be used in the Facilities Master Plan to determine the amount and type of space that will be needed to accommodate the future academic program of instruction and support services. The Facilities Master Plan will cast the projected space need into a sequenced building and facility program that addresses the primary elements of site development and facilities planning through the year 2030.

Deliverables of the Plan

This Plan will deliver the following:

Describe environmental factors that impact the future of the College.

Provide a description and projection of economy and demographics of individuals living in the District service area.

Identify occupations with projected openings into the future.

Describe faculty visions for future curriculum and student services visions for anticipated future services.

Identify general opportunities for instructional program development.

Evaluate the mix of programs vs. labor market and transfer opportunities.

Provide a projection of future weekly student contact hours by discipline.

Framework for the Plan

The planning process principally relied on: (1) an analysis of the external and internal environment of the College including the demographic profile/characteristics; (2) the current and historical performance of the College relative to the areas of academic and support services; (3) the wisdom of those professional educators and administrators who are responsible for delivering the program of instruction and support services; and, (4) input from the CWP consulting team.

Underpinnings

The process for generating the EMP relied heavily on the analysis of the existing program of instruction, the dynamics of the service area, and the vision of future directions articulated by faculty, staff and administrators. It offers a discipline-specific set of recommendations and a broader assessment of the instructional mix of programs.

The 2015 fall semester was used as a "snapshot" in time from which a planning baseline was constructed. Although the College has experienced a downturn in enrollments from the high point of fall 2009, the 2015 fall term was selected as the benchmark because it

was the last complete term of data available to reflect the scope and breadth of the program of instruction and support services.

Analysis was also conducted relative to the demographic and income capacity of the "effective service area" of the College. This was defined as a geographic area with a sufficient and appropriate population base from which students of the future could be drawn. Additionally, a detailed look at the College was provided via an analysis of its external and internal conditions, its past characteristics and trends over a five-year period of fall terms from 2011 to 2015, its current productivity and efficiency, and its future needs for space.

At the present time the College offers a comprehensive curriculum at the approximately 170-acre main campus in Gilroy and an array of offerings at smaller Centers located in the City of Hollister and Morgan Hill. A regional public safety training center program of instruction and a limited number of other college courses are scheduled to open in spring 2017. The District has purchased land in Hollister to eventually build a permanent center there.

Forecasting the future program of instruction was based on determining weekly student contact hours (WSCH) in fall 2015, while the future space needs were largely predicted after defining a future program of instruction.

Activities

The development of the Plan included the following activities:

Referencing and use of the College data files for student basic demographics and enrollment information.

A review of the history and evolution of the College.

An environmental assessment (environmental scan) to consider the present and anticipated impacts both within and outside the College's service area.

The development of a "vision for the future of instructional programs and delivery of student services" derived from qualitative analyses.

The development of growth and enrollment estimates extending to the year 2030.

A review to assure that access and overall success of underprepared and underrepresented groups within the community were considered in the planning process.

The EMP is presented with the intent that it will serve as an educational programming blueprint for the College over the next six to ten years and support a facilities blueprint out to the year 2030.

Gavilan College was originally established in 1919 as San Benito County Junior College. Instruction was offered at Hollister High School. It operated under this title until 1963, when a new community college district was drawn that included both San Benito and southern Santa Clara Counties. Three high school districts- San Benito, Gilroy Unified, and Morgan Hill Unified districts pushed to have the college district boundaries redefined.

Successful passage of a local bond in 1966 provided the needed funds to construct the present, more centrally located campus at Santa Teresa Boulevard in Gilroy. College classes were offered in a temporary location at the Hollister Airport while the first facilities on the 170-acre parcel were being constructed. The Gilroy campus added buildings over time through state funding, with the final new building constructed in 2003.

In 1997 and 1998, satellite sites were established in Hollister and Morgan Hill to augment the offerings at the main campus location in Gilroy. With the 2004 passage of the Measure E facilities bond, Gavilan College had funds to upgrade the existing campus and secure permanent locations in Coyote Valley and San Benito County. These land purchases were completed in 2008. Measure E Bond funds also were used to make improvements in institutional and classroom technology, expanded online services, and improvements in safety, accessibility, and lighting.

The Gavilan Joint Community College District is comprised of 2,700 square miles encompassing southern Santa Clara County and the communities of Coyote, Morgan Hill, San Martin, and Gilroy. The District includes all of San Benito County and the communities of Hollister, San Juan Bautista, Tres Pinos/Pacines.

Mission1

Gavilan College cultivates learning and personal growth in students of all backgrounds and abilities through innovative practices in both traditional and emerging learning environments; transfer pathways, career and technical education, developmental education, and support services prepare students for success in a dynamic and multicultural world.

Principles of Community

As members of the Gavilan College community, we value the worth and dignity of every person, the pursuit of truth, devotion to excellence, acquisition of knowledge, and the nurture of democratic citizenship. We strive to maintain these ideals in an environment of inclusiveness and mutual respect.

The Principles of Community provide the foundation which creates this environment. The expectation is that we maintain the highest ethical standards in order to establish an atmosphere of civility, honesty, cooperation, professionalism and fairness.

Gavilan College aspires to be:

Diverse

We embrace and celebrate diversity in all its forms (the heritage, achievements, uniqueness, and contributions of all our members) and seek to uphold an inclusive, open and enlightened community.

Purposeful

We are a community that maintains a shared commitment to service to society and advancement of knowledge through innovative teaching and learning.

Open

We believe free exchange of ideas requires mutual respect, trust and consideration for our differences.

Just

We are committed to respect for individual dignity and equitable access to resources, recognition and security.

These Principles of Community, reflected in Board Policy 2715, guide the institution's actions. They provide guidelines to follow and are to be considered a living document. Adherence to the Principles of Community is the professional responsibility of all staff. Behavior that is in conflict with the principles will be subject to administrative review.

![]()

1 The mission is evaluated and revised on a regular basis.

Ultimately, Gavilan College is dedicated to fulfilling its mission with compassion, caring and understanding, while respecting all individuals.

Philosophy

Gavilan College is committed to educational excellence. The college aspires to be an exemplary, student-centered community college through leadership, planning, and a commitment to ongoing improvement. Its services and programs are designed to instill the values of critical thinking, life-long learning, cultural understanding, and community service. Gavilan's quality of service to students is closely bound to the quality of the college staff.

Gavilan College strives to accomplish its mission with creativity and innovation and with a proactive, accessible and sensitive presence in the diverse communities it serves. The college is dedicated to fulfill its mission with compassion, caring and understanding and holds, in high regard, the respect and worth of all individuals.

Purpose

Gavilan College offers a wide range of services, including programs of community education, study in the liberal arts and sciences, and study in the pre-professional, business, vocational, and technical fields. To support student success, we offer services that strengthen and augment the learning environment. Courses and programs of study are offered days, evenings, weekends, and online. All offerings are designed to assist students in meeting their educational and life goals.

Visionary Educational Values and Goals Values

An imaginative and nurturing community of learners, fostered through rigorous scholarship, creativity, and personal and professional development.

A college environment and social climate characterized by inclusiveness and mutual respect for all of our students, staff, and community.

Excellence in and promotion of comprehensive programs, services, and activities.

Partnerships that support the educational, economic and social development of the college and the communities we serve.

Goals

To be known for educational excellence

To demonstrate involved and responsive community leadership

To increase our accessibility

To encourage innovative instruction

To lead in the application of appropriate educational technology

To promote a harmonious learning and working environment

The College in Context to its Environment

The official Gavilan Community College District boundaries cover some 2,700 square miles of land located in the southern portion of Santa Clara County and all of San Benito County. The main campus of the College is in the City of Gilroy, along the US 101, approximately 86 miles from downtown San Francisco and 37 miles from downtown San Jose. The western border of the official Gavilan College District area is the Santa Cruz and Monterey County lines. The Merced and Fresno County lines in the east are the ends of the District area and Monterey and Fresno County lines define the southern border.

The three principal cities of the official District service area where most population resides are Gilroy, Morgan Hill, and Hollister. Distances from the campus location to neighboring community colleges are found in Appendix A.

Economy and Employment

The California economy is expected to continue its expansion and growth. In 2014 and 2015 State revenue has been greater than projected. However, the actual revenues for 2016 are slightly behind projections. Nevertheless, for K-14 public education, the adverse economic circumstances of the Great Recession seem to have concluded.

Although the State economy appears to be on the mend and unemployment levels continue to diminish, a recent report from the Public Policy Institute of California (PPIC) observed that if recent trends in higher education and the economy were to continue, by 2030 the State is likely to face a shortage of workers who need some college education up to and including a bachelor’s degree. Their projections, and those of the Centers of Excellence, are that the shortfall of workers with a Bachelor’s degree may be as high as

million to replace workers who will retire. 2 The expected growth of the state economy is projected to create 1 million new middle-skill jobs and 1.4 million replacement jobs for these occupations by 2025.3 Together, these needs are even larger than the projected one-million-worker shortage of college graduates with a bachelor’s degree. The analysis affirms that training beyond high school has become increasingly valuable in the labor market.

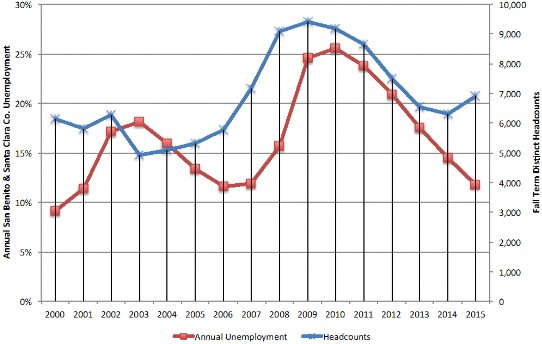

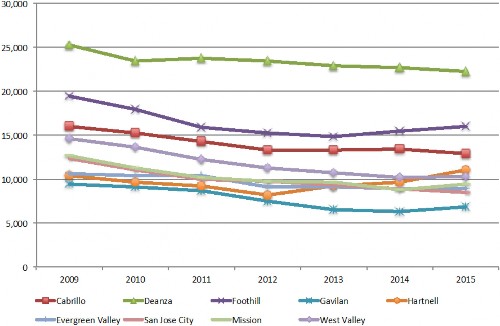

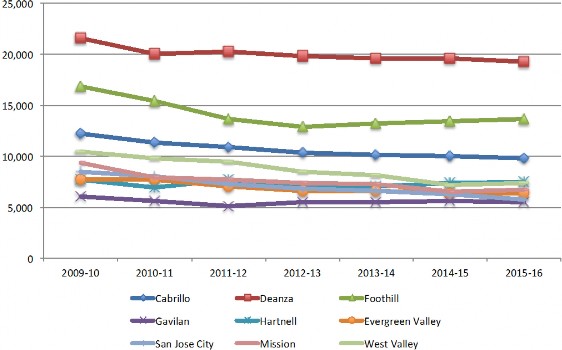

The State of California and the Bay Area experienced the extremely severe recession starting in December 2007. In the years since the start of the Great Recession job growth in California has grown 5.4%, well ahead of the nation at 3.7%. Some parts of the state economy have not fully rebounded to the pre-recessionary levels, but the gross domestic product (GDP) is growing and the Silicon Valley regional economy is leading the state recovery with a job growth of 14.7% between 2007 and 2016.4 The unemployment rate

![]()

2 Johnson, Hans, et. al., “Addressing California’s Skills Gap,” Public Policy Institute of California, April 2016. “California’s Future-Higher Education.” February 2015.

3 Centers of Excellence. Focus on 2025: A 10-year Middle-Skill Occupational Outlook for California.

Retrieved 4/17/16 from http://doingwhatmatters.cccco.edu

4 Allegretto, Sylvia. California’s Labor market: Eight Years Post-Great-Recession. Center on Wage and Employment Dynamics, University of California, Berkeley. May 2016

has dropped substantially and wage rates are increasing, particularly in Santa Clara County. Unfortunately, the housing prices in the area are some of the highest in the nation and the Bay Area Peninsula is short some 60,000 additional housing units to keep pace with population growth. This housing shortfall and regional transportation challenges are severely limiting economic growth.5 In the November 8, 2016 election residents in Santa Clara County overwhelmingly approved Measure A to provide funding for low income housing assistance and other local housing initiatives and also approved Measure B to fund improvements for Caltrain, BART, selected roadways and the regional bicycle infrastructure.6

The Bay Area economy is now rooted in a diverse, competitive set of industries. Technology is transforming industries such as finance, accommodations, and transportation. If the Bay Area were a country, it would be the 21st largest or equivalent to a mid-sized European nation. Twenty-eight of the global Fortune 500 and 29 of the US Fortune 500 companies are headquartered in the Bay Area and none have left the area since 2011. Beyond technology the Bay Area economy has a robust tourism sector.7

The Central Coast Regional (San Benito to Ventura counties) economy is largely driven by tourism, food manufacturing, and agriculture. The region experienced economic downturn before the state slid into the Great Recession. Within the Monterey Bay area employment opportunities were significantly curtailed when the housing market crash began in 2007-08. 8

San Benito County has not fared as well as the Silicon Valley with respect to rebounding from the Great Recession. The unemployment rate has been higher than the statewide and national averages. Although foreclosures were common between 2007 and 2012, they have since declined. The housing market appears to have rebounded, particularly around Hollister. The largest industry in the County is agriculture. It has contributed slow, but steady growth in employment opportunities. While tourism has been a major factor in the economy, the transportation demands on the infrastructure are projected to outstrip capacity. With housing costs at an all time high in the Bay Area, San Benito County has witnessed a sharp increase in urbanization with the largest number of farmland acres lost among the Bay Area counties (Santa Cruz, San Benito, and Monterey). During the Great Recession San Benito County experiences significant housing foreclosures. Since the high point of 2008, foreclosures have tapered off and the median price of homes has become within the grasp of middle-class families.9

![]()

5 Levy, Stephen. The Peninsula Economy. Institute for Regional Studies, Joint Venture Silicon Valley. November 2016.

6 Santa Clara County Registrar of Voters. Election Results. Retrieved November 11, 2016 from http://results.enr.clarityelections.com/CA/Santa_Clara/64404/183053/Web01/en/summary.html

7 Bay Area Council Economic Institute. Promise and Perils of an Accelerated Economy: Bay Area Economic Profile, Ninth in a Series. May 2016.

8 Association of Monterey Bay Area Governments. State of the Region. 2012

9 Association of Monterey Bay Area Governments, Regional Analysis and Planning Services. State of the Region. 2012

Historic counts, 1990 to 2015, of industry employment and labor force by annual average for both Santa Clara and San Benito counties are found in Appendix B of this Plan.

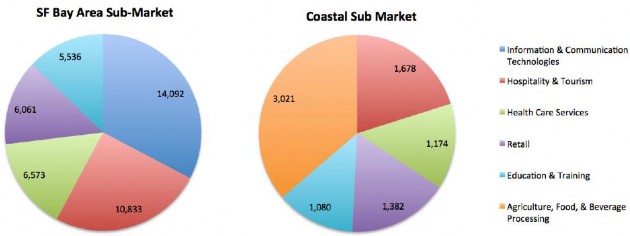

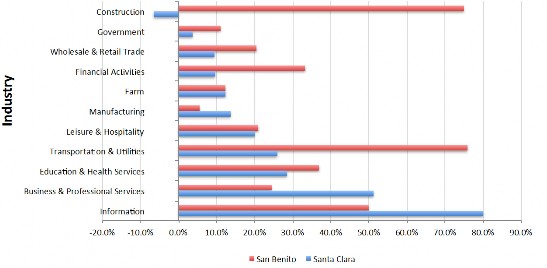

The future is looking a little brighter for San Benito and Santa Clara Counties. Between 2012 and 2022 the California Employment Development Department (EDD) projects an annual average 1.4% increase in jobs. The greatest growth is concentrated in three industrial sectors: (1) professional and business services (25%), particularly in computer system design and related services; (2) educational services (private), health care, and social assistance (25%), with the ambulatory health care services contributing almost 9,000 jobs; (2); (3) information (33%). The following charts document the projections in the two large regional areas and between the two counties for employment opportunities by industry category and illustrate the differences.

Chart 1: San Francisco Bay vs. Coastal Region Projected Job Growth by Industry, 2012- 2022

Source: California Employment Development Department, Labor Market Information; analysis by Cambridge West Partnership, LLC

Chart 2: San Benito-Santa Clara County Projected Job Growth by Industry, 2012-2022

Source: California Employment Development Department, Labor Market Information; analysis by Cambridge West Partnership, LLC

Translating the percentages of growth into actual numbers of jobs within each county illustrates the dramatic difference in the size of future employment opportunities in Santa Clara vs. San Benito counties. The greatest percentage annual projected growth among the eleven industry groups has been marked in bold.

Table 1: Projections of Job Growth by Industry and County 2012-2022

Santa Clara San Benito

North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) Category

Employment Change 2012-

2022

Annual

%

Change

Employment Change 2012-

2022

Annual

%

Change

Business & Professional Services | 90,700 | 5.1% | 230 | 2.4% |

Construction | -2,200 | -0.6% | 540 | 7.5% |

Education & Health Services | 38,800 | 2.9% | 380 | 3.7% |

Farm | 410 | 1.2% | 190 | 1.2% |

Financial Activities | 3,200 | 1.0% | 100 | 3.3% |

Government | 3,300 | 0.4% | 300 | 1.1% |

Information | 43,300 | 8.0% | 50 | 5.0% |

Leisure & Hospitality | 16,300 | 2.0% | 250 | 2.1% |

Manufacturing | 21,100 | 1.4% | 150 | 0.6% |

Transportation & Utilities | 3,300 | 2.6% | 220 | 7.6% |

Wholesale & Retail Trade | 11,000 | 0.9% | 530 | 2.0% |

Total 229,210 2.6% 2,940 2.1%

Source: California Employment Development Department, Labor Market Information; analysis by Cambridge West Partnership, LLC

The workforce, by industry, in the College effective service area (ESA) is described in the following two tables. The tables account for 967,335 adults in the workforce who are

age 16 or older. Employment in the services industry dominates the economy in all of the census places within the area. The proportion of employment in manufacturing and retail trade industries are similar and represent the second and third important sectors.

Table 2: Employment by NAICS, 2016

North American Industry

2016 Adults 16 Years or Older Employed in These Industries Effective

Classification System (NAICS) Category

Service Area

Morgan

Hill Gilroy Hollister

San Martin

w/o ESA Average

Agriculture/Mining | 0.7% | 1.8% | 6.1% | 7.1% | 4.9% | 5.0% |

Construction | 5.0% | 7.2% | 9.0% | 8.7% | 12.8% | 9.4% |

Manufacturing | 18.7% | 15.8% | 11.6% | 11.2% | 18.9% | 14.4% |

Wholesale Trade | 2.2% | 3.3% | 3.1% | 4.7% | 2.1% | 3.3% |

Retail Trade | 9.2% | 9.9% | 12.4% | 12.1% | 8.5% | 10.7% |

Transportation/Utilities | 2.7% | 3.3% | 3.1% | 4.6% | 2.6% | 3.4% |

Information | 3.9% | 2.5% | 1.3% | 1.0% | 1.0% | 1.5% |

Finance/Insurance/Real Estate | 4.7% | 5.8% | 4.0% | 4.1% | 5.1% | 4.8% |

Services | 50.8% | 47.4% | 45.7% | 41.4% | 42.4% | 44.2% |

Public Administration | 2.2% | 3.0% | 3.5% | 5.0% | 1.7% | 3.3% |

count of adults 967,335 21,719 26,506 18,195 3,449 Source: Environmental Systems Research Institute, Market Profile, 2016; analysis by Cambridge West Partnership, LLC

Employment in white-collar occupations dominates the economy in the effective service area and in the three census places (Morgan Hill, Gilroy, and Hollister. Blue-collar occupations provide the second largest group of jobs in Hollister and Gilroy.

Table 3: Adult Employment by Occupation, 2016

Adults 16 Years or Older Employed in These Occupations, 2016 Effective

Occupational Families

Service Area

Morgan

Hill Gilroy Hollister

San Martin

w/o ESA Average

While Collar | 58.4% 17.8% 23.9% | |||||

Management/Business/Financial | 19.2% | 20.5% | 14.1% | 11.5% | 25.2% | |

Professional | 31.7% | 23.4% | 17.1% | 13.4% | 17.6% | |

Sales | 9.3% | 11.6% | 10.7% | 11.4% | 11.1% | |

Administrative Support | 10.0% | 11.5% | 12.1% | 11.9% | 10.4% | |

Services | 15.2% | 16.5% | 18.3% | 19.6% | 16.6% | |

Blue Collar | ||||||

Farming/Forestry/Fishing | 0.4% | 1.0% | 4.7% | 5.4% | 2.3% | |

Construction/Extraction | 3.9% | 5.1% | 7.5% | 8.7% | 6.7% | |

Installation/Maintenance/Repair | 2.2% | 2.5% | 3.7% | 3.4% | 1.4% | |

Production | 4.7% | 4.5% | 5.4% | 6.0% | 3.5% | |

Transportation/Material Moving | 3.4% | 3.5% | 6.3% | 8.6% | 5.2% |

count of adults 967,335 21,719 26,506 18,195 3,499

Source: Environmental Systems Research Institute, Market Profile, 2016; analysis by Cambridge West Partnership, LLC

The population in Gilroy, the largest city in the Gavilan College District service area, has grown faster than all cities in Santa Clara County. Job growth is expected to be modest over the next decade and will likely occur in retail, transportation, construction, hospitality, information, and health care industries. The proximity to Silicon Valley makes Gilroy an attractive location for businesses seeking lower-cost locations for expansion. Developing more affordable housing units in Gilroy will be a challenge for municipal authorities. Roughly 40 percent of the housing stock in Gilroy is rented and rent levels are more affordable than purchase prices.10

![]()

10 City of Gilroy. Gilroy Economic Development Strategic Plan. February 19, 2014

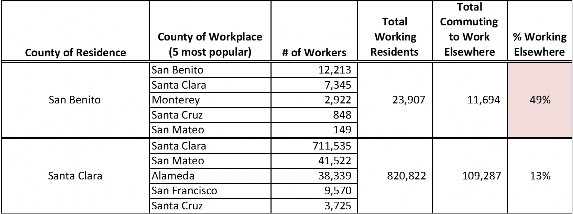

One of the striking features of the economic dynamics in the region is the number of workers who commute into other counties for work, particularly from San Benito into other counties.

Table 4: Top Five Commuting Destinations 2006-2010

Source: Bay Area Census, American Communities Survey Commute Flows Survey 2006-10; analysis by Cambridge West Partnership, LLC

The analysis of commuting habits of those who live in the three primary cities within the official district service area indicates a great deal of commuting has been taking place. In the case of Morgan Hill, two-thirds of the residents commute to other places for work.

Half of the workers in Hollister commute elsewhere to work while 56% of those who live in Gilroy commute elsewhere for work.

Table 5: City Level Commuter Flows 2006-2012

Works in | Total Working Population | Total Commuting to Work Elsewhere | % Working Elsewhere | |||||

Gilroy | Morgan Hill | Hollister | San Jose | |||||

City of Residence | Gilroy | 8,210 | 1,690 | 230 | 4,425 | 18,495 | 10,285 | 56% |

Morgan Hill | 945 | 5,285 | 90 | 5,455 | 15,953 | 10,668 | 67% | |

Hollister | 1,275 | 515 | 5,960 | 1,170 | 11,903 | 5,943 | 50% | |

Source: Bay Area Census, American Communities Survey Commute Flows Survey 2006-10; analysis by Cambridge West Partnership, LLC

Implications for the College

In the broader regional San Francisco Bay Area the dominant growth industry is in information and communications technologies followed by hospitality and tourism. Conversely in the greater regional area of the Costal counties the dominant growth is in agriculture, retail, and construction materials and services

industries. Employment opportunities are projected to continue into the future but they may not be in the cities located within the Gavilan official district service area. Although entry-level preparation for many jobs in some of these industries commonly does not require education beyond high school, there may openings for which the College needs to prepare individuals with career and technical certificates and Associate Degrees.

Future job opportunities and economic growth in construction, trade, and education/health care/social assistance industries, plus a much improved real estate market with affordable housing characterize the future of San Benito County. Business and professional services and information industries, but a costly real estate market, characterize the future of Santa Clara County. The College can contribute to the economy of counties by preparing students for transfer to four-year institutions. For those students who want to “transfer to the workplace” upon completing a certificate or Associate Degree, the College can offer instruction that will equip them with in-demand job skills.

The distinctive mix of advanced manufacturing, information and communications technologies, and research and development businesses places a premium on Science, Technology, Engineering, Mathematics, and Medicine (STEMM) fields of study. The College has well-established programs of study in these disciplines but will be called upon to increase the numbers of graduates.

The municipal and county governments need to facilitate construction of affordable housing in order to stimulate the future population growth. If they are successful, that will bring a new audience for the College to woo.

Higher Education Policy

Several key policy decisions will influence the California Community College system in the coming years. These public policies both provide opportunities for the colleges but in some cases impose constraints.

The Completion Agenda

In July 2009, President Obama articulated that the American Graduation Initiative (AGI) has a goal of increasing the percentage of U.S. residents who earn high-quality degrees and credentials from the present rate of 39 percent to a rate of 60 percent by the year 2025. The goal is to make the U.S. competitive in the global marketplace. In the private sector, employers have been increasingly screening applicants for employment by requiring college degrees for positions that previously did not require a degree.11

After President Obama has pushed to increase college graduation rates across the nation, Complete College America, a non-profit organization, was formed to advance this mission. It has enlisted support from leaders in 34 states to ensure greater numbers of students acquire degrees.

![]()

11 Doug Lederman. “Credential Creep Confirmed” Inside Higher Education. September 9, 2014; Karin Fischer. “A College Degree Sorts Job Applicants, but Employers Wish It Meant More,” Chronicle of Higher Education. March 8, 2013 p. 26-29

The President’s challenge to the nation has not been ignored in California. The Community College League of California (CCLC) launched an “alternative futures” project, 2020 Vision for Student Success, to respond to the national graduation goal by identifying policy and practice changes that could be implemented to increase student achievement. To contribute its part toward achieving the national graduation goal, California needs to produce a total of 1,065,000 degrees or certificates per year to 2025. That translates to producing an additional 23,000 degrees and certificates per year, a 5.2% annual increase.12 The California Public Policy Institute has repeatedly informed state policy makers that the State faces a skills gap.13

In August, 2014, the Board of Governors for the California community college system joined in the completion effort by announcing a goal to increase the numbers of students earning certificates, degrees, or transferring to four-year institutions by nearly a quarter of a million over the next ten years. For academic year 2013-14 the system awarded 190,314 certificates and degrees, a 40 percent increase from 2009-10 and an all-time high for the system. The Gates, Ford, Lumina, and Kellogg Foundations as well as the Carnegie Corporation of New York fund their collective work and the efforts of others to promote more college graduates. Collectively, there are more than two-dozen major entities that have sponsored initiatives to promote college completion.14

Federal Policy and Funding Initiatives

The Congress passed the Higher Education Opportunities Act in 2008. Subsequently, a series of new federal regulations have been issued to improve program integrity where Title IV financial aid funds are involved. Regional accrediting bodies are now expected to provide closer scrutiny of member institutions on a range of new topics. The Higher Education Act has been due for renewal and no one can predict its future direction.

The Obama administration and the U.S. Department of Education have announced a new emphasis for their involvement with career and technical education through a transformation of the Carl D. Perkins Career and Technical Education Act of 2006 as it comes due for renewal. Although the Act has not yet been renewed, the desired new directions will promote greater alignment between CTE programs and labor market needs as well as collaboration with K-12 and employers. Differences in the current provisions of the Perkins Act and the proposed changes were announced as long ago as April 2012.15

In July 2014 the Congress enacted the Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act (WIOA) by a wide bipartisan majority as the first legislative reform in the past 15 years of the public workforce system. This legislation took effect on July 1, 2015 with regulatory rules written by the Departments of Labor (DOL), Education (DOE), and

![]()

12 2020 Vision: A Report of the Commission on the Future, (Sacramento, CA: Community College League of California, 2010)

13 Public Policy Institute of California. California’s Future: Higher Education. January 2016 and Higher Education in California. April 2016.

14 Alene Russell. “A Guide to Major U.S. College Completion Initiatives,” American Association of State Colleges and Universities, October 2011.

15 U.S. Department of Education, Office of Vocational and Adult Education. Investing in America’s Future: A Blueprint for Transforming Career and Technical Education. April 2012.

Health and Human Services (HHS). In general, the legislation eliminates 15 existing federal training programs and focuses on streamlining programs, reporting, and administration. WIOA keeps the basic structure of the prior legislation, with components covering occupational training, adult basic education, literacy and English language acquisition, vocational rehabilitation, and the national system of public employment offices and services. Key features and opportunities of the WIOA legislation include requirements for more unified planning between state and local authorities to address regional labor markets, a common set of performance measures, and promotion of best practices including contextualized adult basic education, ESL, and attainment of industry- recognized certificates.

The White House convened a series of higher education summits in order to promote change in higher education policy and practice. Attention was given to greater access, particularly for low-income students, the completion agenda, college outcome performance measures, constraints to the ever-rising costs of high education, and other topics of interest to the federal government. To encourage more participation in postsecondary education the President used his 2015 state of the union address to offer a proposal, along the lines of the current policy in Tennessee, that the federal government help each state to make attendance at a community college free of tuition. By mid-spring 2016 there had been launched 27 new free community college programs.16

While it has been announced that some new federal resources will be allocated for use by community colleges, the Congress is currently also struggling to restrain spending and to reduce debt levels. The long-term impact remains to be seen, but federal aid now has a lifetime limit and is also limited to a maximum number of credit hours represented by 150% of the credits required for the program of study the student is pursuing. For a community college associate degree 150% would equate to 90-semester credit hours.

Veterans on the G.I. Education Bill may be more limited in the credit hours funded by that program. In the FY2016 budget the President proposed that the maximum award under the Pell Grant program would increase and new rules would require students to make progress in their programs by passing an increasing percentage of their total course load. In a December 2015 budget deal the Congress unexpectedly agreed to increase the Pell grant maximums and provide additional funds to college access programs for needy students (TRIO and GEAR UP). President Obama has signed an executive order to align the monthly repayment rate of federal loans to the level of future wages earned by the student. That may ease the burden of debt for students and make the act of borrowing for a college education more feasible for prospective students. The President has also declared a policy to not enforce deportation on children of illegal immigrants meeting certain conditions and to provide work permits for those children.

Regional Accreditation Initiatives

In part, stimulated by prior federal government actions, all regional accrediting bodies are insisting that greater attention be given to student learning outcomes.

![]()

16 White House Press Release. White House Launches $100 Million Competition to Expand Tuition-Free Community College Programs that Connect Americans to In-Demand Jobs. April 25, 2016.

These new areas are in addition to the traditional goals of accreditation that are:

Providing assurance to the public that the education provided by the institution meets acceptable levels of quality

Promoting continuous institutional improvement

Maintaining the high quality of higher education institutions in the region

Implementation of the new ACCJC 2014 accreditation standards has introduced a number of changes, including the requirement to create a quality focus essay to guide future improvement efforts. 17 The changes also echoed some of the national discussions about educational quality and accreditation.

California Community College Initiatives for Student Success

The following State initiatives are intended to increase student success rates:

The Board of Governors’ basic skills initiative seeks to enable more students to overcome their academic deficiencies.

Targeted funds for student equity and student success and support programs.

Additional legislation, SB1440 Student Transfer Achievement Reform or STAR Act in 2010, simplified the process of transferring from a community college to a school in the California State University (CSU) system. This program provides a pathway for students to follow so that they can be admitted to a CSU with junior status. It has been complemented by SB440 in 2013, which further incentivizes transfer students to complete an associate degree.18

The long-standing commitment to basic skills education has sometimes suffered for lack of adequate funding. However, in the 2016-17 budget there was a $30 million increase in this targeted allocation. In May 2016 the Chancellor’s Office announced a request for applications to be awarded up to $60 million from Proposition 98 funds to implement or expand evidence-based innovations and redesign in the areas of assessment, student services, and instruction in order to improve the progression rate of basic skills students into college level instruction. Known as the Basic Skills and Student Outcomes Transformation Program, the funds were awarded to 43 colleges.

As second pool of funds was awarded to basic skills partnerships between community college districts or a consortium of districts and at least one California State University for the purpose of developing efficient and effective methods of coordinating remedial instruction and services. Successful applicants centered their proposals on evidence-based remedial education, instructional redesign, or program expansion. Five project proposals were awarded a total of $10 million.

Perhaps the most potentially far-reaching set of recommendations for change in policy and practice were included in the report from the California Community College Chancellor’s Office Student Success Task Force. The group proposed eight areas of focus

![]()

17 Accrediting Commission for Community and Junior Colleges. Preparing for A Comprehensive Visit. Workshop materials presented on October 15, 2014.

18 Campaign for College Opportunity. Keeping the Promise: Going the Distance on Transfer Reform.

March 2016.

with 22 recommendations. The Legislature passed the Student Success Act (SB 1456) in August 2012 and the governor signed it shortly thereafter. The measure did the following:

Commissioned the development of a uniform placement exam for students;

Directed colleges to provide students with orientation, assessment, placement and counseling services;

Required students to identify an educational goal (such as degree or certificate for transfer to a four-year university) and complete an educational plan;

Required colleges that receive student support service funds to complete and post a student success scorecard showing how well the campus is doing in improving completion rates, especially by race, ethnicity, gender, and income;

Established minimum academic progress standards for students to receive Board of Governors fee waivers, but also developed an appeal process.

The Task Force recommendations came in the wake of a severe shortfall in resources for California’s public higher education institutions. Therefore, implementation of these ideas was delayed.

Funds allocated for 2015-16 enabled the Chancellor’s Office to provide support to colleges that develop a student success and support plan (formerly matriculation) built around some of the recommendations arising from the Student Success Task Force. The provision of effective core services (orientation, assessment and placement, counseling, academic advising, and early intervention or follow-up for at-risk students) has been found to improve students’ ability promptly to define their educational and career goals, complete more of their courses, persist to the next term and achieve their educational objectives in a timely manner.19 As new priority enrollment rules were made effective in fall 2014, one of the incentives for students to complete the core services was the potential loss of priority enrollment or withholding of an enrollment opportunity.

One Student Success Task Force recommendation was the development of a robust common assessment instrument. The assessment services will also include data collection and course placement guidance, but the placement cut scores will remain a local decision. Working groups of faculty from the disciplines of English, Math and ESL have been involved in drafting competencies that address the full range of prerequisite skills found in the curriculum. The common assessment initiative has a “go live” target of the 2016- 17 academic year, pending a successful pilot experience.

The effort to exploit technology to support student success blossomed into the Educational Planning Initiative that was launched to help colleges meet the requirements for student success and support program funding by providing an individual comprehensive educational plan for all students. The initiative is also intended to enhance the counseling experience by inducing students to take more responsibility for their educational program plans and to have counseling expertise used only to verify the planning. A degree audit system to provide transcript, articulation and curriculum

![]()

19 Eva Schiorring and Rogeair Purnell. Literature Review Brief: What We Know About Student Support 2nd

Ed. Research and Planning Group of the California Community Colleges. Fall 2012.

inventory elements is to be provided to help both students and counselors. As a by- product, it is hoped that the numbers of unnecessary units accumulated by students will be reduced. A single sign-on portal is intended to be the student’s point of access to this system that is described as a service-oriented experience in which some existing services will be complemented by new services yet to be produced. The project has a “go live” target of the 2016-17 academic year, pending a successful pilot experience.

The legislation implementing some of the recommendations of the Student Success Task Force, SB 1456, requires the coordination of student equity plans and student success and support programs. Student equity identifies groups of students needing more help and focuses on services and instruction for new and continuing students through to completion whereas student success and support programs focus on services for entering students and identifies individual students who need more help. Interest in student equity is not new as the Board of Governors adopted a student equity policy in 1992, but financial support for planning and interventions has not always been available or adequate. In 2014 the Legislature appropriated $70 million for student equity purposes, added foster youth, veterans, and low-income students as target populations, and required specific goals and activities to address disparities and coordination of them with other categorical programs. The traditional populations or variables researched for student equity planning are: age, disability status, gender and ethnicity. Unlike the student success and support program funding, dollars for student equity interventions do not require a match of funds or in-kind effort from the colleges. Funding for both efforts was increased for 2015-16 after the May 2015 budget revision. An additional increase is proposed for 2016-17.

The governor’s interest in online education garnered an appropriation of $56.9 million over 55 months to launch the Online Education Initiative for the community colleges. The initiative is intended to increase access to more online courses created by community college faculty members and to provide students well-designed resources that will improve their chances of a successful learning experience. Part of the work in this initiative is to improve student readiness to engage in the learning experience through online instruction and to provide tutoring support for those students. Those two components have had a successful pilot project “go live” in spring 2015. A common course management system launched among the pilot colleges in fall 2015. Within the initiative are efforts to assist faculty in several professional development ways- creating of online course content, teaching strategies for the online environment, course design standards, and course review training.

Adult Education Initiative

The governor’s initial proposal for the adult education programs to be absorbed into the community colleges met with stiff opposition in the Legislature. A compromise was fashioned to improve and expand the provision of adult education through regional consortia that would eliminate redundancy and craft pathways into higher education for interested students. Instruction in parenting, home economics and classes for older adults were explicitly excluded from this funding. The 2015 AB104 legislation provided a block grant of funds (AEBG) to support action plans to close gaps for adult learners in four

areas: (1) elementary and secondary basic skills; (2) ESL and citizenship for immigrant populations; (3) adults with disabilities; and (4) short-term career and technical education.

Career and Technical Education Initiatives

In 2012 the Legislature passed SB 1402 which the Governor signed to signal intent to recast and rewrite the economic and workforce education division programs and services. The new direction requires industry sector strategies that align collaboratively with labor markets on a regional basis. The Chancellor’s Office translated these policy directions into a four-part initiative called Doing What Matters (DWM) for Jobs and the Economy. Governor Brown has been generous in funding this work and his 2016-17 budget proposals offered $200 million more to expand access to career and technical education as well as to implement new regional accountability structures.

The Silicon Valley schools within the Bay Area Community College Consortium (BACCC) selected the three priority sectors or clusters and two emerging sectors. The priority sectors were (1) Information, Communications, and Technologies; (2) Healthcare; and (3) Advanced Manufacturing. The emerging sectors were (1) Energy, Construction, and Utilities; and (2) Advanced Transportation and Renewables.

The initial phase of DWM was designed to dovetail with the State Workforce Plan created by the California Workforce Investment Board. Some funding from the DWM initiative was awarded to the regions to enhance existing CTE programs and to support regional collaborative work. The second phase of this initiative applies common accountability metrics to gauge the extent to which the efforts have “moved the needle.” A system of common metrics was then developed that includes student momentum points and leading indicators of success. A third phase promotes bringing innovation and best practices to scale. The overriding message of the DWM initiative is to prompt collaborative action within regions to prepare students for work in critical industry sectors.

The 2014-15 State budget provided a one-time pool of $50 million that helped the DWM initiative incentivize the colleges to develop, enhance, retool, and expand CTE offerings in response to regional labor market needs and to stimulate additional regional collaboration. The budget for 2016-17 offers $200 million to be allocated among the regions for the work of preparing students to enter the middle-skills workforce.

In 2013 SB 1070 (California Partnership Academies) was enacted to establish an economic and workforce development program for the community colleges. It requires the Board of Governors, the Chancellor’s Office staff and the colleges to assist economic and workforce regional development centers and consortia to improve, among other things, career-technical education pathways between high schools and community colleges. Contracts and competitive grants funded by the program through 2015 were jointly administered to improve linkages and CTE pathways between high schools and community colleges.

Additional efforts to promote career pathways from high schools to the community colleges were enshrined in the 2014-15 budget as it passed the California Career Pathways Trust Act. Some $250 million was provided in the form of one-time competitive grants. These funds were made available to school districts, county superintendents of schools, directly funded charter schools, regional occupational centers or programs operated by a joint powers authority, and community college districts. The Legislature allocated a second round of funding for the Trust with applications for competitive grants to be implemented in academic years 2015-16 and 2016-17.

The most recent legislation to promote collaboration, AB 288, signed into law on October 8, 2015, authorizes the governance board of a community college district to enter into a College and Career Access Pathways (CCAP) partnership with the governing board of a school district to offer or expand dual enrollment opportunities for students who may not already be college bound or are from underrepresented groups in higher education. The goal is to develop a seamless pathway from high school to community college for career- technical education or preparation for transfer, improving high school graduation rates, or helping high school students achieve college and career readiness.

In November 2015 the Board of Governors culminated a yearlong effort to revisit the ways in which career and technical education was delivered as a means to prepare students for middle skills jobs. The Task Force they commissioned provided 25 recommendations in seven broad areas. Full details are available at http://bit.ly/1lpCGOM. The recommendations are expected to shape policies from the Board of Governors over the next few years.

Dual Enrollment

The most recent legislation to promote collaboration, AB 288, signed into law on October 8, 2015 to take effect in January 2016, authorizes the governing board of a community college district to enter into a College and Career Access Pathways (CCAP) partnership with the governing board of a school district. The partnerships are to offer or expand dual enrollment opportunities for students who may not already be college bound or are from groups underrepresented in higher education. The goal is to develop a seamless pathway from high school to community college for career-technical education or preparation for transfer, improving high school graduation rates, or helping high school students achieve college and career readiness. The following are the highlights of the legislation:

Community colleges can assign priority enrollment and registration to high school students in a CCAP with no fees to pay;

Courses during the regular high school day can be restricted to high school students and do not have to meet the normal open enrollment standard;

Courses with no open seats on campus cannot be offered at high schools through the CCAP;

Basic skills math and English can be offered through CCAP but only for students who are not at grade level in that subject; and

Community colleges can claim FTES if the high school student is qualified for full high school apportionment without using hours of the college course.

Many of the initiatives discussed above have benefited from generous funding associated with the continued recovery of the California economy. Apportionment base funding has been restored, categorical funding has been advanced, and one-time funds have been provided. That funding trend continued into the May 2016 revision of the Governor’s 2016-17 Budget. However, it is believed that the California economy is nearing the point when a normal economic expansion period should end and resources provided should be used to position each college for the future.20

New Growth Funding Formula

Apart from targeted funds described above, the SB 860 legislation from 2014 will impact the allocation of apportionment funds for growth to the districts by using a new formula starting in 2015-16. The legislation directed that growth would be based on each community’s need for access to their community college as determined by local demographics. Need within each district’s official boundaries is to be determined by three primary factors: number of adults within each district who are without a college degree, and the number of individuals who are disadvantaged as evidenced by unemployment and measures of poverty; Pell grant award annual percentage.21 Gavilan College is projected to have a constrained apportionment growth rate of 0.51%.22

Implications for the Colleges:

A broad array of governmental and private organizations is promoting the urgency for postsecondary institutions to produce more graduates. It has been estimated that the State economy will be short in excess of two million graduates with a bachelor’s degree or postsecondary education short of the bachelor’s degree by 2025. As a public agency the College should embrace that public agenda with vigor.

As the federal government seeks to achieve a more balanced budget there is still financial support for students and incentives for institutions to increase student success and prepare more students to compete in a global economy. However, these incentives come with performance expectations. The College may have opportunities to enhance resources and it should act upon those opportunities.

After many years of debate, several federal workforce-training programs have been consolidated and a new direction emphasizing regional efforts and agency collaboration has emerged in the Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act (WIOA) legislation. As of fall 2016 the Carl Perkins legislation has not yet been reauthorized nor has the Higher Education Act been reauthorized. The College should monitor trends in federal to be in a position to take advantage of any new direction.

![]()

20 Mario Rodriguez, Acting Vice Chancellor for Finance. 2016-17 May Revise Letter to the System.

21 Day Toy, Vice Chancellor for Finance. “Growth Funding Allocation Formula,” Consultation Digest. November 20, 2014. “California Community Colleges Growth Funding Allocation Model” power point presentation to the Association of Chief Business Officers Conference. October 27, 2014.

22 Fred Harris, Vice President for Administrative Services. Gavilan College Budget Workshop 2016-17.

Slide presentation created August 29, 2016

The regional accrediting commission, ACCJC, is following federal direction with requirements it has imposed on member institutions. Recent state legislation intended to induce intentionality into institutional planning and to hold public colleges accountable for performance on state priorities are in a similar spirit to the accreditation expectations. Attention should be given to tracking student achievement and learning performance and acting upon areas were performance does not meet ACCJC expectations.

Starting three years ago State legislation (SB 1440) created a remarkable framework to facilitate transfer to a campus within the California State University (CSU). Community college and CSU faculty throughout the state have risen to the occasion to forge transfer model curriculums (TMCs). Gavilan College achieved its expected target, but there may be more that could be done to facilitate transfer.

Particular state attention has been given to re-crafting matriculation and other student services along the lines of recommendations from the Student Success Task Force. Although matching funds are required, attention must be given to student success concerns. Participating institutions will be required to use a common placement assessment instrument when it is developed if funds are accepted. The College has a series of opportunities to improve services and student success by participating in these new state programs.

A serious revisiting of online instruction as a delivery mode is being funded in the State. While the College has been building an array of online classes, the online education initiative is a promising opportunity in which the College should consider participating.

Adult education has long been neglected as a public service in the state. The AEBG legislation provides fresh funding to promote regional cooperation and elimination of redundancy with incentives to focus the instruction on preparing vulnerable citizens for more effective participation in the workforce. This legislation, combined with the increased funding level for selective noncredit curriculum to equal the level of credit instruction starting in FY 2015-16, presents a unique opportunity to make a very substantial difference in the service area. The College should grasp the opportunity to implement the planning work done by the regional consortium.

Several opportunities are unfolding for career and technical education both within and outside of the Doing What Matters for Jobs and the Economy initiative from the Chancellor’s Office. Several dedicated funding sources are promoting inter-segmental cooperation and regional approaches to this type of instruction. The College should position itself to fully engage the various opportunities in this curriculum.

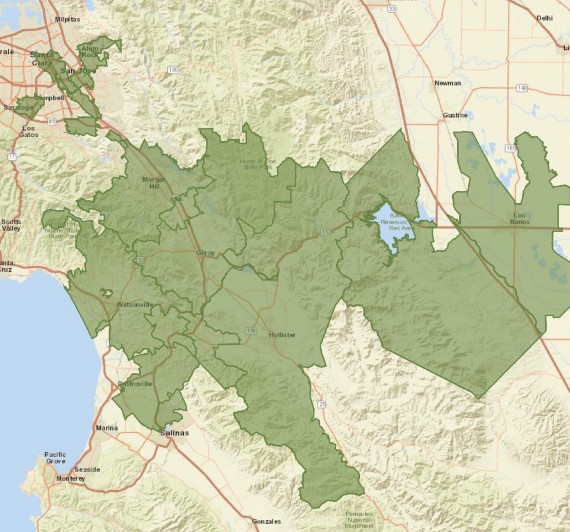

First Day of Fall Term

Population Served: GCCD Effective Service Area

Within San Benito and Santa Clara Counties, the official boundaries of the District are the areas described in this graphic.

Chart 3: Official Gavilan Community College District Boundaries

Source: Gavilan College Office of Institutional Research. Factbook, 2012

In 2010 the area population numbered approximately 178,400 people. By 2018 the official District service area population is projected to 189,0709. Although the official District service area includes 12 zip codes, the College has been attracting student enrollments from a wider area.

Effective Service Area

Based upon an analysis of residential zip codes reported by enrolled students over the last five fall terms (2011 to 2015), the effective service area for Gavilan College encompasses 11 cities. Seventy-five percent of the student headcount comes from zip codes that are inside the official District area.

Table 6: In-District vs. Outside-District Origination

Category | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | Average |

% In-District | 68.1% | 71.4% | 78.8% | 81.5% | 76.1% | 75.2% |

% Out-of District | 31.9% | 28.6% | 21.2% | 18.5% | 23.9% | 24.8% |

Source: California Community College Chancellor’s Office, MIS Referential Files; analysis by Cambridge West Partnership, LLC

Individuals from the 21 zip codes represented in these areas account for 80% of the students participating at the College in the fall terms from 2011 to 2015.

![]()

![]()

Table 7: Key Zip Codes for Student Origination

Distinct Headcounts, Fall Terms |

| |||||||||||

In- Dist | Zip | City | 2011 | 2012 |

2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2011 to 2015 % Change | Total | Average | % of Total | Cumula- tive % |

Y | 95020 | Gilroy | 2,374 | 2,172 | 2,167 | 2,167 | 2,242 | -5.6% | 11,122 | 2,224 | 29.9% | 29.9% |

Y | 95023 | Hollister | 2,068 | 1,841 | 1,772 | 1,729 | 1,797 | -13.1% | 9,207 | 1,841 | 24.7% | 54.6% |

Y | 95037 | Morgan Hill | 1,050 | 940 | 885 | 904 | 944 | -10.1% | 4,723 | 945 | 12.7% | 67.3% |

Y | 95046 | San Martin | 198 | 193 | 180 | 166 | 183 | -7.6% | 920 | 184 | 2.5% | 69.8% |

Y | 95045 | San Juan Bautista | 110 | 112 | 109 | 101 | 111 | 0.9% | 543 | 109 | 1.5% | 71.2% |

Y | 95021 | Gilroy | 102 | 114 | 100 | 90 | 98 | -3.9% | 504 | 101 | 1.4% | 72.6% |

Y | 95024 | Hollister | 70 | 73 | 95 | 71 | 69 | -1.4% | 378 | 76 | 1.0% | 73.6% |

95076 | Watsonville | 58 | 51 | 51 | 55 | 66 | 13.8% | 281 | 56 | 0.8% | 74.3% | |

93906 | Salinas | 61 | 35 | 40 | 41 | 60 | -1.6% | 237 | 47 | 0.6% | 75.0% | |

93635 | Los Banos | 40 | 31 | 41 | 53 | 64 | 60.0% | 229 | 46 | 0.6% | 75.6% | |

95123 | San Jose | 50 | 34 | 44 | 42 | 49 | -2.0% | 219 | 44 | 0.6% | 76.2% | |

93907 | Salinas | 27 | 39 | 32 | 40 | 60 | 122.2% | 198 | 40 | 0.5% | 76.7% | |

95110 | San Jose | 31 | 70 | 13 | 35 | 38 | 22.6% | 187 | 37 | 0.5% | 77.2% | |

Y | 95038 | Morgan Hill | 49 | 31 | 27 | 39 | 35 | -28.6% | 181 | 36 | 0.5% | 77.7% |

95004 | Aromas | 35 | 31 | 27 | 30 | 34 | -2.9% | 157 | 31 | 0.4% | 78.1% | |

95111 | San Jose | 21 | 15 | 29 | 30 | 52 | 147.6% | 147 | 29 | 0.4% | 78.5% | |

95127 | San Jose | 25 | 15 | 23 | 32 | 38 | 52.0% | 133 | 27 | 0.4% | 78.9% | |

Y | 95139 | San Jose | 24 | 26 | 20 | 16 | 23 | -4.2% | 109 | 22 | 0.3% | 79.2% |

95008 | Campbell | 24 | 18 | 33 | 13 | 18 | -25.0% | 106 | 21 | 0.3% | 79.5% | |

95122 | San Jose | 16 | 11 | 23 | 20 | 35 | 118.8% | 105 | 21 | 0.3% | 79.7% | |

95112 | San Jose | 13 | 13 | 20 | 28 | 29 | 123.1% | 103 | 21 | 0.3% | 80.0% | |

Source: California Community College Chancellor’s Office, MIS Referential Files; analysis by Cambridge West Partnership, LLC

These zip codes represent a limited number of cities as shown on the following table. Table 8: Key Cities for Student Origination

In-

Distinct Headcounts, Fall Terms

2011 to

2015 %

% of All

Cumula-

Dist City 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015

Change Total Average

Zips Total

tive %

Y | Gilroy | 2,476 | 2,286 | 2,267 | 2,257 | 2,340 | -5.5% | 11,626 | 2,325 | 31.2% | 31.2% |

Y | Hollister | 2,138 | 1,914 | 1,867 | 1,800 | 1,866 | -12.7% | 9,585 | 1,917 | 25.7% | 57.0% |

Y | Morgan Hill | 1,099 | 971 | 912 | 943 | 979 | -10.9% | 4,904 | 981 | 13.2% | 70.1% |

Y | San Martin | 198 | 193 | 180 | 166 | 183 | -7.6% | 920 | 184 | 2.5% | 72.6% |

Y | San Juan Bautista | 110 | 112 | 109 | 101 | 111 | 0.9% | 543 | 109 | 1.5% | 74.1% |

San Jose | 156 | 158 | 152 | 187 | 241 | 54.5% | 894 | 179 | 2.4% | 76.5% | |

Salinas | 88 | 74 | 72 | 81 | 120 | 36.4% | 435 | 87 | 1.2% | 77.6% | |

Watsonville | 58 | 51 | 51 | 55 | 66 | 13.8% | 281 | 56 | 0.8% | 78.4% | |

Los Banos | 40 | 31 | 41 | 53 | 64 | 60.0% | 229 | 46 | 0.6% | 79.0% | |

Aromas | 35 | 31 | 27 | 30 | 34 | -2.9% | 157 | 31 | 0.4% | 79.4% | |

Y | San Jose | 24 | 26 | 20 | 16 | 23 | -4.2% | 109 | 22 | 0.3% | 79.7% |

Campbell | 24 | 18 | 33 | 13 | 18 | -25.0% | 106 | 21 | 0.3% | 80.0% |

Source: California Community College Chancellor’s Office, MIS Referential Files; analysis by Cambridge West Partnership, LLC

Demographic attributes for the effective service area associated with the College are provided in the following table. Population growth between the year 2010 and 2021 for the effective service area is estimated to be 12.6%. The projected annual rate of population growth in the next several years (2016 to 2021) is 1.20%. The median age, in the low to mid-30s, will be relatively young. Household income and home values continue to increase.

Table 9: Effective Service Area Demographics

Gavilan Effective Service Area | 2016 to 2021 | ||||||

Annual Rate | 2000 to 2016 | 2010 to 2021 | |||||

Element | 2000 | 2010 | 2016 | 2021 | of Change | % Change | % Change |

Population | 689,709 | 731,662 | 776,179 | 823,866 | 1.20% | 12.5% | 12.6% |

Group Quarters | 13,532 | ||||||

Households | 200,497 | 217,802 | 228,404 | 242,006 | 1.16% | 13.9% | 11.1% |

Average Household Size | 3.39 | 3.30 | 3.34 | 3.35 | -1.5% | 1.5% | |

Median Age | 33.0 | 33.7 | 34.9 | ||||

Median Home Value | $521,075 | $570,400 | |||||

Median Household Income | $68,630 | $78,400 | |||||

Per Capita Income | $27,547 | $29,991 |

Source: Environmental Systems Research Institute, Demographic and Income Profile and Market Profile; analysis by Cambridge West Partnership, LLC

An extended population projection for the effective service area is illustrated in the following table.

Table 10: Effective Service Area, Extended Population Projections

Extended Population Projection Annual Rate

Area | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | 2025 | 2026 of | Change |

Gavilan Effective Service Area | 833,752 | 843,757 | 853,883 | 864,129 | 874,499 | 1.20% |

![]()

Source: Environmental Systems Research Institute, Market Profiles; analysis by Cambridge West Partnership, LLC

This larger effective service area is illustrated in the following graphic. Chart 4: Gavilan College Effective Service Area

Source: Environmental Systems Research Institute, Market Profiles; analysis by Cambridge West Partnership, LLC

The three primary individual locations within the District official service area have different rates of growth with Gilroy growing most rapidly, but Morgan Hill is close behind. In fall 2016 residents in both Gilroy and Morgan Hill approved ballot measures designed to limit or slow down growth and to promote a strategy of “in fill” as opposed to sprawl at the edges of each city.

Table 11: Census Place Populations in the District Official Service Area

Population Counts & Projection

2016 to 2021

Annual Rate

Area/Census Place 2000 2010 2016 2021 of Change

Effective Service Area | 689,709 | 731,662 | 776,179 | 823,866 | 1.20% |

Morgan Hill | 33,733 | 37,882 | 43,296 | 47,854 | 2.02% |

Gilroy | 42,560 | 48,821 | 54,338 | 60,959 | 2.33% |

Hollister | 33,954 | 34,928 | 37,627 | 40,059 | 1.26% |

San Martin | 6,504 | 7,027 | 7,372 | 7,775 | 1.07% |

Source: Environmental Systems Research Institute, Market Profiles; analysis by Cambridge West Partnership, LLC

An extended population projection for the three primary places within the District’s

official service area is illustrated on the following table.

Table 12: District Official Service Area Census Places, Extended Population Projections

Extended Population Projection Annual Rate

Area 2022 2023 2024 2025 2026 of Change

Gavilan Effective Service Area | 833,752 | 843,757 | 853,883 | 864,129 | 874,499 | 1.20% |

Morgan Hill | 48,821 | 49,807 | 50,813 | 51,839 | 52,887 | 2.02% |

Gilroy | 62,379 | 63,833 | 65,320 | 66,842 | 68,399 | 2.33% |

Hollister | 40,564 | 41,075 | 45,289 | 45,860 | 46,438 | 1.26% |

San Martin | 7,858 | 7,942 | 8,742 | 8,836 | 8,930 | 1.07% |

Source: Environmental Systems Research Institute, Market Profiles; analysis by Cambridge West Partnership, LLC

The 2006 landmark legislation, AB32, set absolute statewide limits on greenhouse gas emissions and called for local governments to set reduction targets. The 2008 sustainable communities and climate protection act, SB 375, supports the state climate action goals through requirements for coordinated transportation and land use planning to reduce travel demand. In response to these legislative directives the Association of Bay Area Governments (ABAG), Metropolitan Transportation Commission (MTC), Bay Area Air Quality Management District, and the Bay Conservation and Development Commission developed the Plan Bay Area 2040 Preferred Scenario, an update to the work started in 2010, and the Association of Monterey Bay Area Governments (AMBAG) developed in June 2011 the Envisioning the Monterey Bay Area: A Blueprint for Sustainable Growth and Smart Infrastructure Among other things these plans seek to stimulate new residential housing construction to use existing vacant land within existing jurisdictions.

In fall 2016 residents in Morgan Hill and Gilroy restated their interest in managing the rate of housing construction and population increase in those communities by passing measures S and H respectively. In contrast, the City of Hollister had a six-year, state- mandated growth moratorium imposed in 2002 due to shortcomings in the municipal wastewater capacity. Subsequently, the Great Recession from 2008 to 2012 discouraged any residential construction. But, as of 2016 there is a building boom in Hollister as the City has 31 building projects, totaling 2,480 units scattered throughout the City. In addition, the Santana Ranch project for 1,100 homes to be constructed on land just outside the city limits had been previously approved by the County of San Benito. Some 1,200 housing units had been approved for construction in the 1990s but had not been built. The City cannot predict when or to what extent developers will actually construct the homes they have been permitted to complete. 23

Relatively speaking, the cost of housing in the South San Francisco Bay region is high and projected to continue rising with the largest increases predicted for San Benito County.

Table 13: Median Home Values

Median Home Values 2016 vs. 2021

Element 2000 2010 2016 2021 % Change

Effective Service Area | $521,075 | $570,662 | 9.5% | ||

Santa Clara County | $518,241 | $596,708 | $711,608 | $737,942 | 3.7% |

Morgan Hill | $682,519 | $740,011 | 8.4% | ||

Gilroy | $546,188 | $599,542 | 9.8% | ||

San Martin | $837,743 | $874,049 | 4.3% | ||

San Benito County | $342,477 | $288,083 | $468,368 | $521,391 | 11.3% |

Hollister | $374,543 | $432,411 | 15.5% | ||

San Juan Bautista | $587,500 | $689,560 | 17.4% |

Source: Environmental Systems Research Institute, Market Profiles. 2016. California Association of Realtors. 1990-2017 Historic Median Prices of Homes; analysis by Cambridge West Partnership, LLC

Except for Hollister, the majority of owner-occupied homes in all of the other cities within the College service area are valued in 2016 at $400,000 or more.

![]()

23 Cheek, Marty. “Morgan Hill, Gilroy Voters Will Decide Future Growth in Region,” Morgan Hill Life. October 26 and November 8, 2016. Chadwell, John. “City Manager Says New Homes Have Been Planned for Decades,” Benito Link. October 9, 2016. Paxton, Mary. Personal Correspondence. City of Hollister Development Services, November 21, 2016 and Michael Kelly, Personal Correspondence. San Benito County Planning, November 21, 2016

Table 14: 2016 Owner Occupied Housing Unit Values

Value Range

Eff Service Area

2016 Owner Occupied Housing Units by Value Morgan

Hill San Martin Gilroy Hollister

San Juan Bautista

<$50,000 | 3.7% | 2.6% | 2.3% | 3.2% | 4.8% | 0.9% |

$50-$149,999 | 4.8% | 2.3% | 1.2% | 1.3% | 3.7% | 2.9% |

$150-$249,999 | 7.1% | 1.6% | 1.0% | 3.4% | 14.8% | 3.3% |

$250-$399,999 | 17.8% | 7.8% | 2.7% | 17.1% | 31.6% | 23.3% |

$400-$749,999 | 45.5% | 43.9% | 30.8% | 53.5% | 38.2% | 35.0% |

$750-$1M+ | 21.1% | 41.7% | 62.0% | 21.6% | 6.9% | 34.7% |

Source: Environmental Systems Research Institute, Market Profiles; analysis by Cambridge West Partnership, LLC

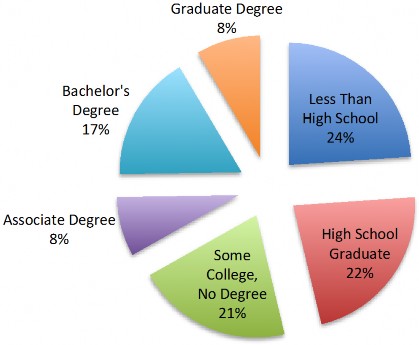

Within the effective service area 46% of the residents have either less than a high school diploma or only a high school diploma. Another 21% completed some college but did not complete an Associate Degree. Both of these groups of residents are prime candidates for the instruction offered by the College.

Chart 5: Effective Service Area, Educational Attainment in 2016 for Adults Age 25 or Older

Source: Environmental Systems Research Institute, Market Profile; analysis by Cambridge West Partnership, LLC

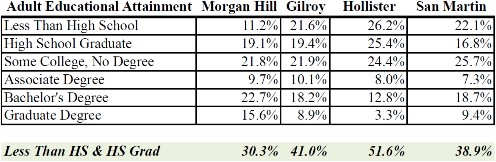

The census place locations within the District official service area have different adult educational attainment distributions with the Hollister and Gilroy having the largest portion of adults with less than high school completion attainment.

Table 15: Census Places Adult Educational Attainment, 2016

Source: Environmental Systems Research Institute, Market Profile; analysis by Cambridge West Partnership, LLC

In response to the AB86 Adult Education legislation, educational need indicator data was assembled to facilitate adult education program planning in the regional consortia area.

The socio-economic data they received to support planning is displayed in the following table representing the educational needs of the most vulnerable citizens in the larger region.

Table16: Educational Needs of Adults in the Gavilan Regional Consortium for Academic and Career Education Services

AB86 Educational Needs of Adults | ||||||||

ESRI 2014 Data | 5-Yr ACS 2009-2013 Data | |||||||

Regional Consortia | 2014 Regional Population 18 years + | Poverty | No High School Diploma | HS Grad | Some College | Unemploy- ment | Illiteracy | ESL (English Language Learners) |

Gavilan's Regional Consortium | 132,143 | 7,976 | 22,393 | 30,240 | 27,666 | 7,053 | 13,511 | 15,284 |

Percent of 2014 Population | 6.04% | 16.95% | 22.88% | 20.94% | 5.34% | 10.22% | 11.57% | |

Sources: U.S. Census Bureau American Community Survey and U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Educational Statistics- National Assessment on Adult Literacy; analysis by the AB86 Work Group

Compared to San Benito County, the Gavilan College effective service area (ESA) contains slightly more low-income households. Compared to Santa Clara County, the Gavilan ESA contains six percent more low-income households.

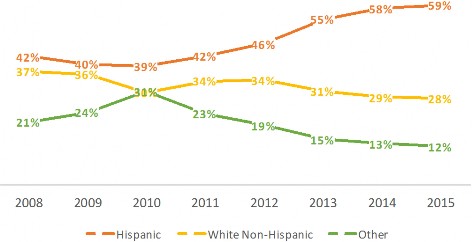

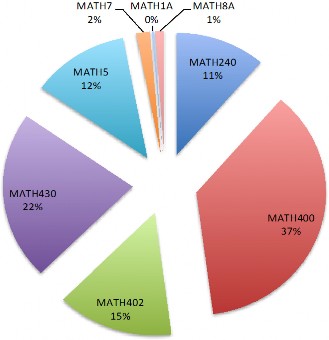

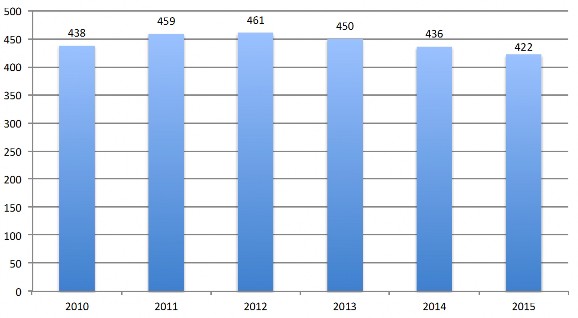

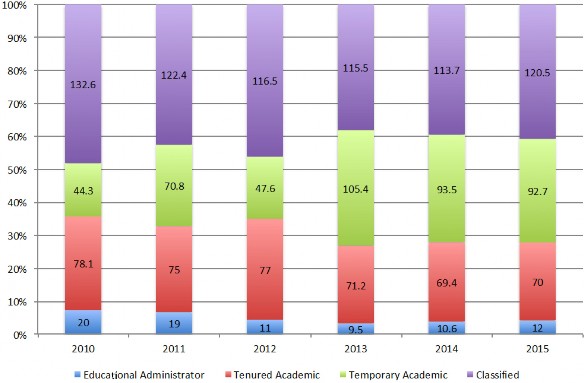

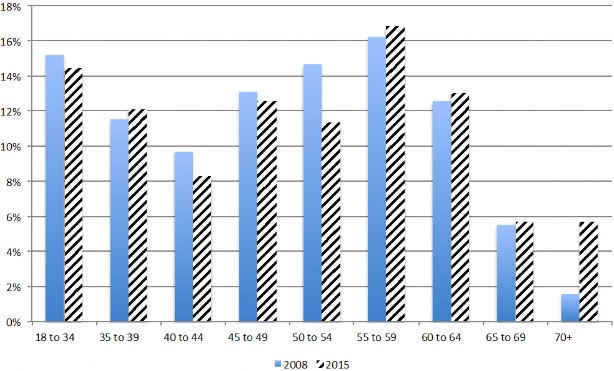

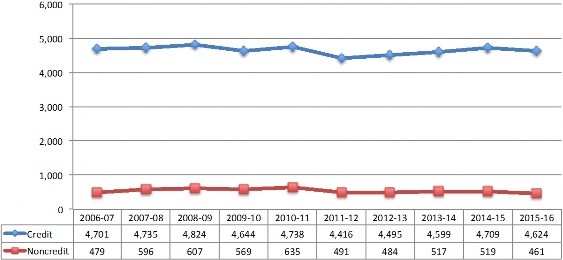

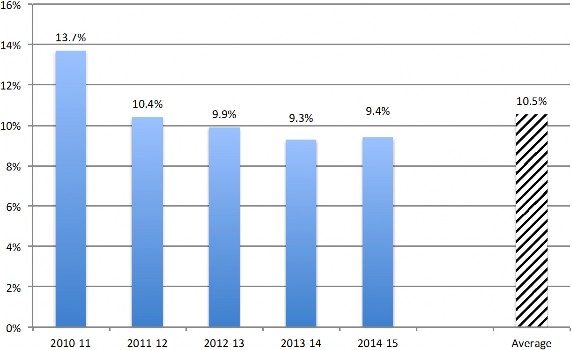

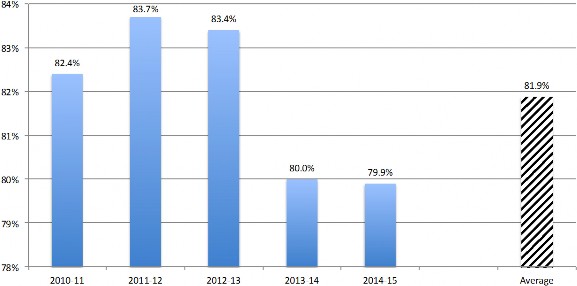

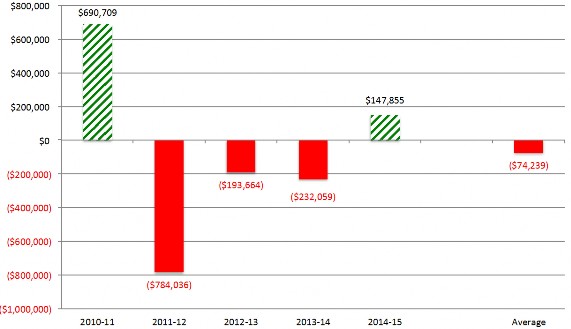

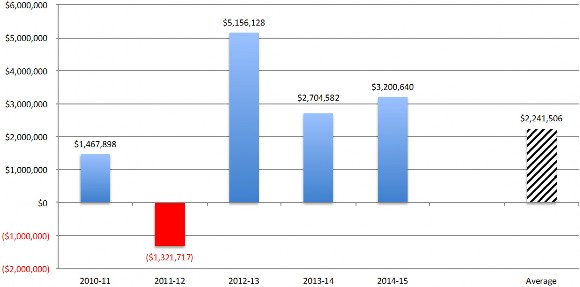

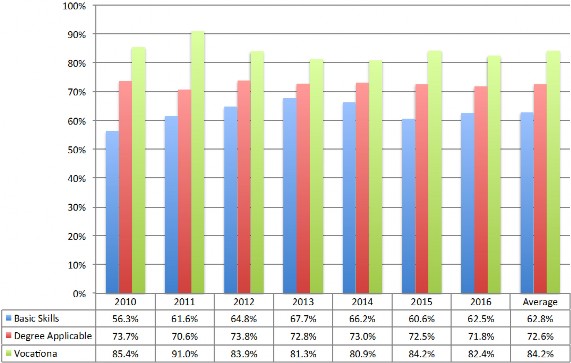

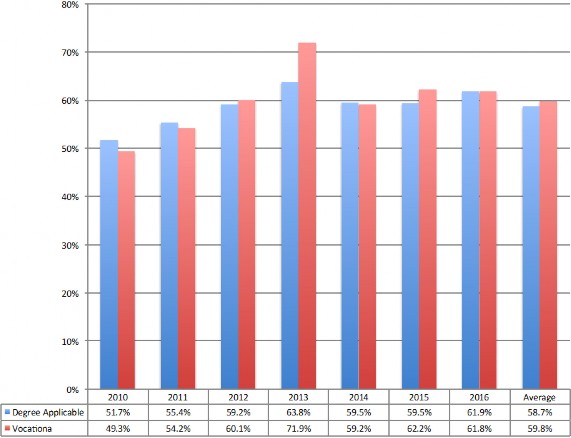

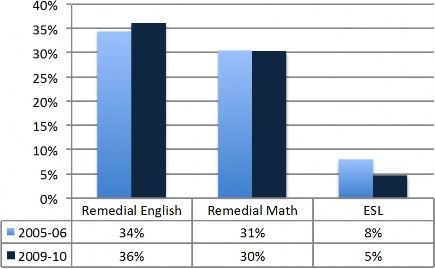

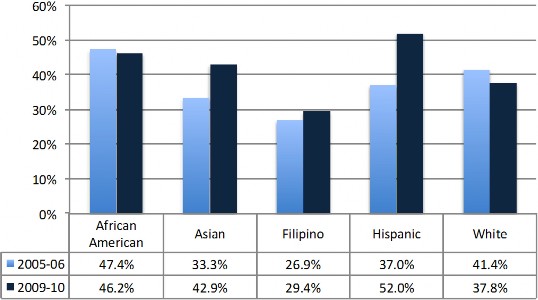

Table 17: Comparative Household Incomes